When I meet new people, we readily go through the usual initial exchange:

“Hello. My name is <INSERT FAVORITE NAME HERE>.” A hand is extended for a handshake.

“A pleasure to meet you! My name’s Solomon. Like the King, but no relation.” A polite chuckle escapes the other person to my rather comical ice breaker.

“So, what do you do for a living?”

“Oh, I’m a chemistry teacher.”

And then I brace for it…

“GAWD!!!! I hated chemistry in high school!! No offense, of course, but I just didn’t get any of it.” Of course, I am watching their faces contort, as if the person just ate something that made rancid food appealing, and the hands gesticulate wildly.

At first, I couldn’t understand the reaction. Which is to say that I appreciated that not every subject is everyone’s cup of tea, and science certainly can fall into that realm. But, to not understand anything about chemistry, or physics, or mathematics, just did not compute for me (if you pardon the pun), and struck me as a gross exaggeration. After getting the same reaction more times that I can count, I pondered as to why people would feel the way that they did about science and mathematics. Especially since to me, it is rather logical… for the most part…

I have found that one of the primary reasons that people “don’t get” chemistry, physics, or mathematics, is because of the type of thinking and executive function processing STEM subjects demand. There are two sides of this kind of thinking.

First, when confronted with a scientific or mathematical problem given in a classroom setting, or a situation encountered in the natural world, one must not only identify all of the ideas that are in play, but how each ideas manifests itself, and how each idea interact with one another.

Second, if there is a quantitative analysis involved (solving equations, trying to find how much of something, and so on), rarely is it a one-step process. Typical problems demand multiple steps, utilization of several skills, and equations, all of which need to be applied in a logical order.

Clearly, if you ask a person to do this without any training and meaningful support, it is akin to asking that person to simultaneously cook a gourmet meal, file their tax returns and accompanying schedules, help their best friend, who is ranting about a life crushing event, do the laundry, making sure to separate everything out, set the washer to the right temperature, and add the correct detergent, write out a grocery list, create plans to go out on Saturday night, all while making sure that you catch the latest episode of Grey’s Anatomy, so that you are “in the know” the next day at the water cooler.

Okay, my hypothetical is a bit farcical, I admit. But consider: any one of those tasks is quite simple and doable by themselves. It is when you compound the situation by multitasking that the proverbial wheels come flying off of the wagon. And consider further: eventually, we realize that with such a litany of tasks, it makes much better sense if we stop trying to do everything at once, and develop a list, prioritizing in order what should be done, and in what order. We end up getting everything done faster, with much less stress, and the meal that the person tried to cook is actually worth enjoying!

What are the implications for science and mathematics? I believe that people who profess to “not get it” (and sometimes, “…and I never will!”) were never given the chance to get a clear sense of understanding because they were never taught how to think through, or plan, how to solve problem or explain a physical phenomena. Everything became overwhelming. Things didn’t make sense. And add to that that some concepts are simply esoteric (how can an electron be a particle, like the billiard ball that I see in the textbook, and a wave, like ripples in pond or like sunlight, at the same time?), and it is a recipe for disaster.

In a previous post on The Lost Step to Solving Physics Problems, I discussed adding a critical step in the process of working through a physics, or chemistry, problem. The steps I outlined are a bird’s eye view of solving problems. When confronted with problems that require more than one step, we need to add to our process. Which brings us full circle, and shows the utility of our real world example. We need to scaffold!

Take a step back from the problem. Think of a plan of attack to solving it. Look at your given information – what relationships can use deduce? What quantities can you calculate based on what you know? Map out the steps that will get you from A to B to C to D to…to the answer of what is being asked! You will quickly find that you are just taking a complicated problem, and breaking it down into those simple, one step problems that you practiced over and over in class. The skill that you need to become adept at is how to link those easy, one step problems for one specific idea or quantity, so that you create a map to get you from what you know to what you want to know.

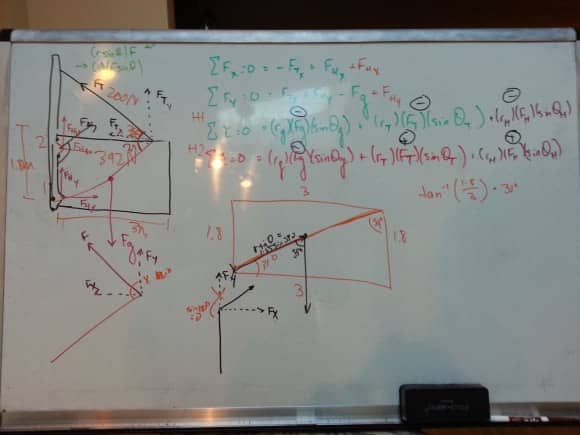

I will conclude with an example from just this past weekend. Here is a picture of a “board,” that shows the work of a student in AP Physics B:

It looks like quite a bit of work is going on, and if you didn’t like physics before, I am sure that this isn’t helping the cause.

In this picture, there are only two small equations, being applied over and over again (look to the bottom two long equations – same variables!), we applied the concept of static equilibrium, which told us what our equations would equal to, and did some algebra and trigonometry. That’s it!

And the student was surprised that that was all there was, until I made her break everything down and explain each force, write the simple equation for calculating each force, which she knew how to do handily, and then just put the pieces together.

Took her a while to finish, but she became only one of two people in her class that could solve the problem.

And she admits – there are just a lot of pieces in play at once, and that is what is so hard! Not the actual physics.

Just keep breaking things down into little pieces, and see how the pieces to the puzzle connect! Have your teacher, or tutor, work with you to effectively learn the skill!